Don’t Be Overly Optimistic about CCUS in the United States

Regulatory and public acceptance issues will likely continue to constrain project development.

Protracted federal rulemaking and slow Class VI permitting represent a significant obstacle to advancing CCUS projects in a timely manner, which is further complicated by an uneven regulatory landscape at the state level, driven by the uncertainty around federal CO2 pipeline regulations. Moreover, even amid existing bipartisan consensus over the role of the CCUS industry, the November presidential election is likely to exacerbate the current challenges if Donald J. Trump wins the contest and launches a deregulation campaign.

Missing federal regulations

The lack of critical regulatory updates limits carbon storage options and fuels public concerns and regulatory uncertainty at the state level. In November 2021, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act mandated the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) to publish offshore CO2 storage regulations within 1 year from the enactment of the legislation. After two and half years, the work is still going on, and the Biden administration’s latest update of the regulatory agenda has no deadline for the adoption of the planned offshore carbon storage rules. The lack of the enabling framework prevents companies from tapping the CO2 storage potential of the Gulf of Mexico outside state waters, which falls under the federal jurisdiction. According to the estimates by the Department of Energy (DOE), GoM’s oil and gas reservoirs alone could store up to 20 billion tons of carbon dioxide. This volume would be more than enough to sequester annual emissions from the Gulf Coast industries, which account for around 20% of total US emissions, or almost 1.2 billion metric tons in 2022.

Separately, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) is yet to release updated CO2 pipeline safety standards, which is critical to improving regulatory environment and mitigating public concerns at the state level. In May, the Illinois state legislature passed the bipartisan SAFE CCS Act, which would establish a 2-year moratorium on the construction of CO2 pipelines that could be lifted in July 2026 or when the PHMSA finalizes its safety regulations, whichever comes first. There are currently 7 proposed carbon storage projects in Illinois, which could face delays as a result of this pause in the construction of CO2 transport infrastructure. In addition, in Iowa, where the Utilities Board has recently approved Summit Carbon Solution’s CO2 pipeline, the reliance on outdated PHMSA’s safety standards is also a source of public concerns, which could lead to legal challenges against the regulators and operator.

EPA’s procedures require streamlining

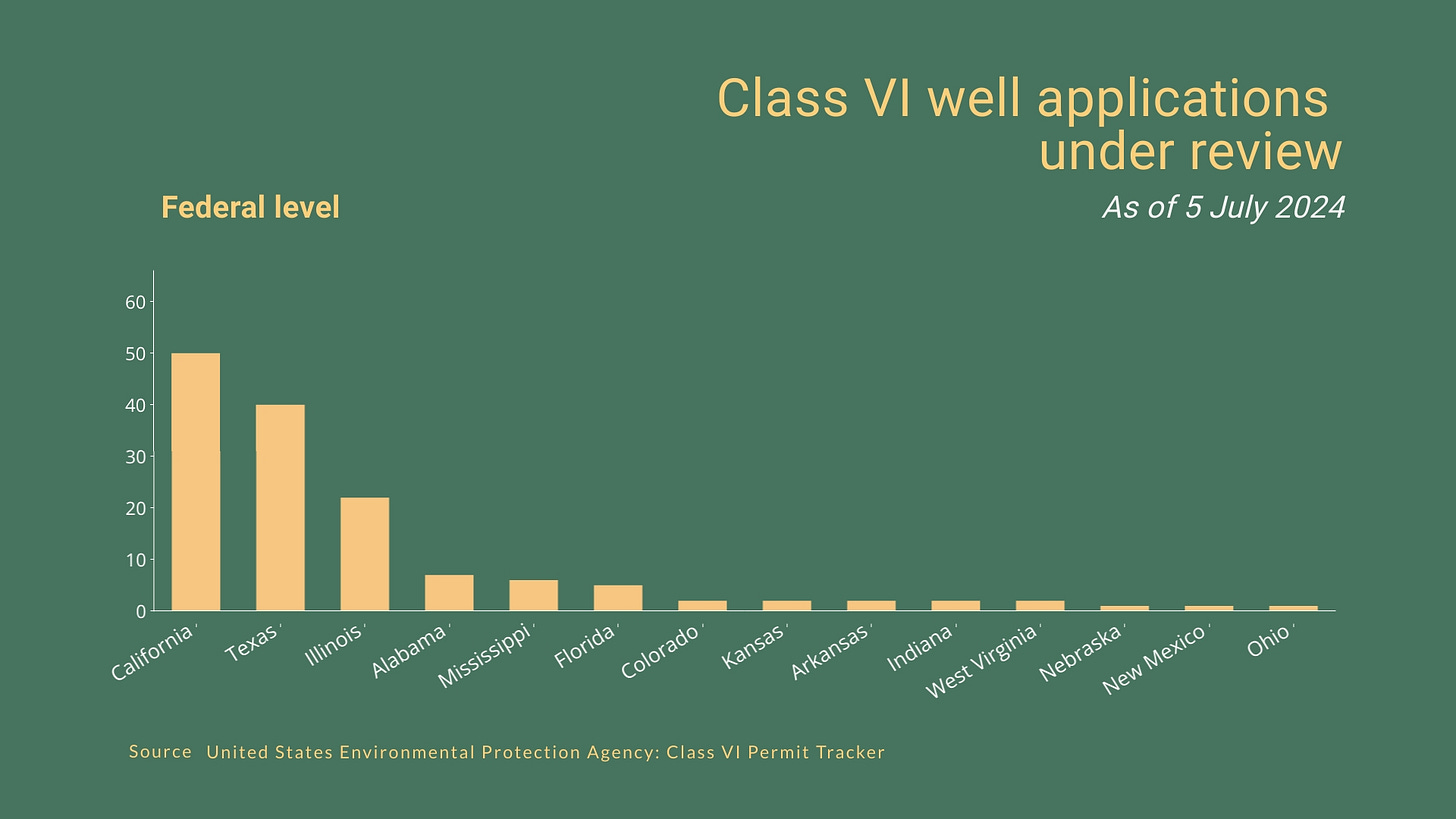

Despite additional funding and increased administrative capacity, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is struggling to accelerate Class VI permitting and primacy applications processing. Currently, the federal agency is reviewing 49 projects with 145 Class VI well applications. Transferring the primary authority over Class VI wells to state regulators would significantly reduce the EPA’s burden, but this also seems to be a challenge. In 2023, 23 states and two tribes expressed an intention to seek Class VI primacy, but only three states – Arizona, Texas, and West Virginia – are now at the pre-application stage. The timeline for the EPA’s final ruling is highly uncertain, given the agency’s track record: it spent four years on North Dakota’s application, eight months on Wyoming’s and over two years on the most recent primacy application from Louisiana. Such a slow process increases the risk that dozens of proposed projects would have a limited timeframe to capitalize on or completely miss the benefits of the 45Q tax credit, which is set to expire in 2033.

In the meantime, permitting procedures at the state level could also require improvements. To date, North Dakota has issued five Class VI permits, with three more applications pending. In Wyoming, it took Frontier Carbon Solutions ten months to obtain three Class VI permits, and another application from Tallgrass has been under review since December 2023. In turn, Louisiana, with its newly acquired primacy, has 65 Class VI applications from 26 projects (the largest number in the country), and the state is yet to demonstrate its ability to process such applications efficiently. Moreover, Louisiana is facing a lawsuit from three environmental groups – the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, Healthy Gulf, and the Alliance for Affordable Energy – that seek to reverse the EPA’s decision to grant Louisiana Class VI primacy. If the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit upholds the case, all pending applications in Louisiana will be in limbo, with projects likely to be put on hold until the state and federal authorities address the issue.

What if: Collateral CCUS damage under the Trump administration

The potential second Trump administration and the Republican Party in general do not pose a threat to CCUS projects. However, the fallout from Trump’s likely deregulation push could have negative effects on the CCUS regulatory environment. As in 2017, Trump is likely to focus on undoing the legacy of the previous Democratic administration via executive action, leading to the reversal of Biden’s executive orders and potentially putting on pause any unfinished rulemaking, including BOEM’s offshore storage rules and PHMSA’s CO2 pipeline standards.

Separately, Trump could rollback important environmental regulations, such as methane rules by the EPA and Bureau of Land Management (BLM). In this scenario, federal agencies are expected to be inundated with lawsuits from environmental groups, which is likely to affect workflows, forcing their staff to deal with legal challenges instead of developing and finalizing regulations. Erratic federal rulemaking coupled with Trump’s chaotic approach to staffing, when federal officials come and go, is likely to create an uncertain policy and regulatory environment for various industries, including CCUS. This uncertainty is likely to feed into state-level actions aimed at regulating carbon transportation projects, potentially making it harder for developers to navigate regulatory requirements across multiple subnational jurisdictions.