Coupling CO2 Storage with Geothermal: Policy, Regulatory and Public Acceptance Issues

Existing policy and regulatory frameworks will likely need adjustments to encourage the deployment of new technology.

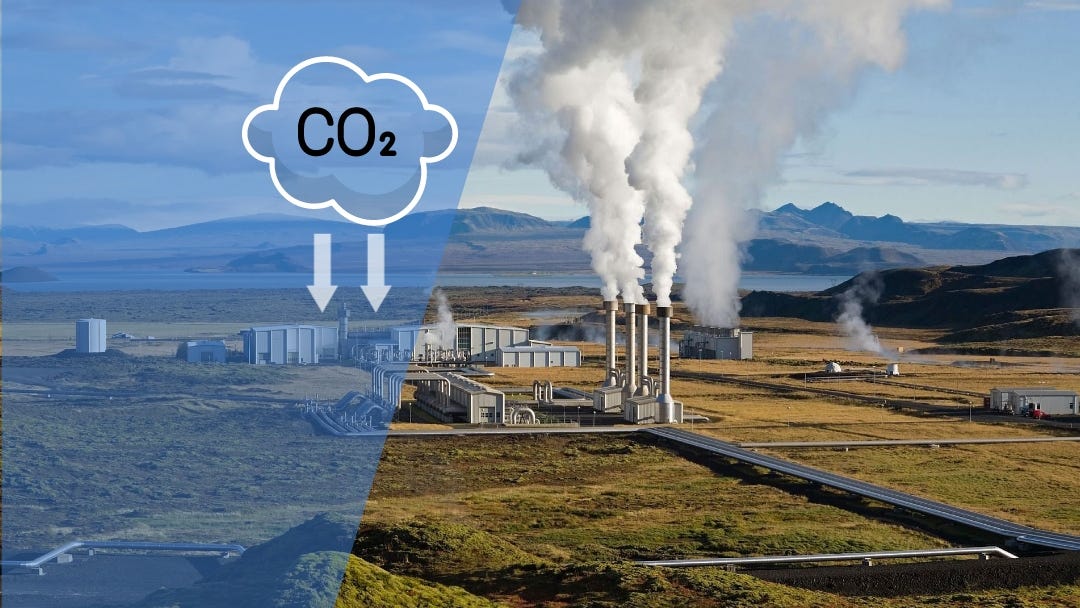

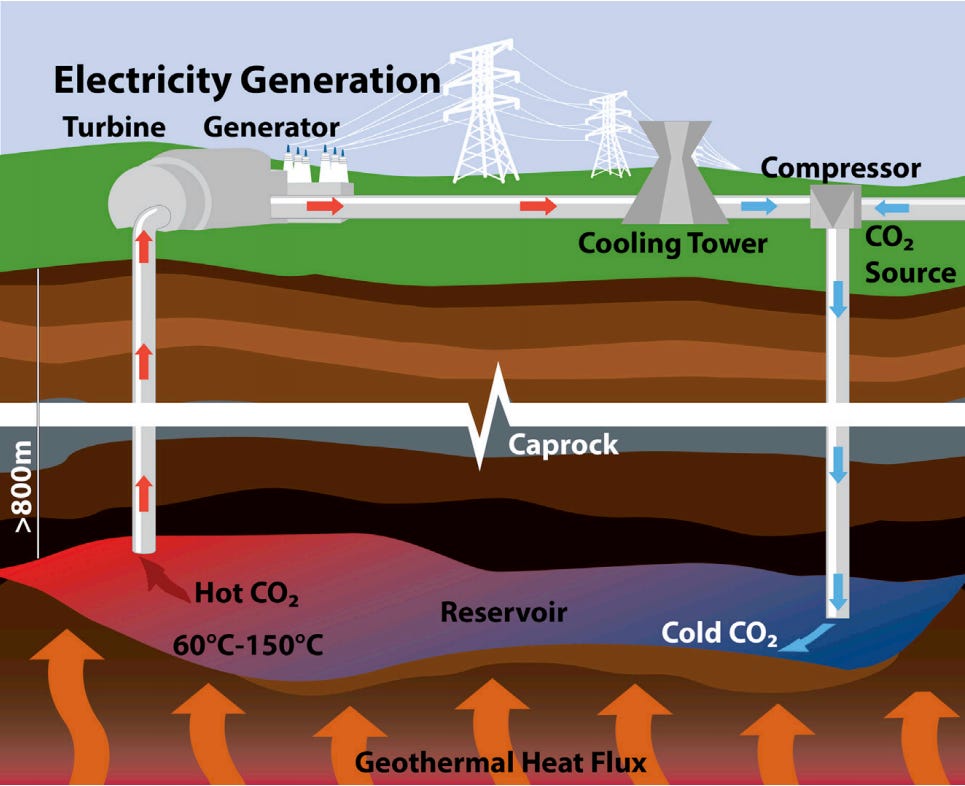

The proposed technology offers an opportunity to utilize captured carbon dioxide and generate clean energy. According to the researchers from the Ohio State University, the use of CO2 as a working fluid in sedimentary basins facilitates access to low-grade heat. In a CO2 Plume Geothermal (CPG) power plant, a portion of the geologically stored carbon dioxide is circulated in a closed system between the subsurface and surface to produce thermal energy. This heat could be used directly or converted to electricity in a geothermal power plant, before CO2 is reinjected into the subsurface. Given the low-temperature sedimentary resources, it is likely to be more beneficial to deploy CPG as a dispatchable resource to support variable wind and solar generation as opposed to baseload operations that would deplete the heat too quickly.

There are multiple technical and economic challenges associated with CPG that require further research and testing. For example, the researchers from Carbon Solutions found that in North America, the locations with lowest-cost CO2 storage do not necessarily align with the locations with lowest-cost CPG. This will likely require adjustments to electricity prices or the buildout of a CO2 pipeline network to connect lowest-cost CPG with capture facilities. As the IPCC suggests that an economically feasible transport distance for carbon dioxide pipelines is 300 km, the cost of the transport infrastructure is also likely to affect the attractiveness of a CPG facility. Other challenges include preventing and monitoring CO2 leakage from the target reservoir; predicting subsurface flow of injected CO2; and controlling plume migration to allow for continuous CO2 injection and extraction. Currently, there are no pilot CPG projects that would demonstrate the viability of the technology. However, in March 2023, ETH Zurich formed a consortium to develop a CPG demonstration project, which now includes Ad Terra Energy, Petrobras, Shell, and Holcim, indicating the interest of large industry players in this new technology.

Policy considerations

The deployment of CPG will likely require the combination of different incentives to facilitate the advancement of such projects. Carbon taxes and emission trading schemes are likely to work for both CCUS and geothermal power generation as they encourage emissions reduction. If separate tax credits exist for CCUS and geothermal projects, the developers of CPG facilities could be allowed to combine them in order to ensure a maximum benefit. However, CCUS incentives typically have different amounts depending on whether the captured CO2 is utilized or geologically sequestered, which could create confusion in the case of CPG as it includes carbon dioxide utilization and storage. Governments will need to create clear and comprehensive guidelines to ensure that each segment in the CPG value chain receives an adequate amount of support.

Regulatory considerations

The hybrid nature of CPG projects is likely to complicate permitting and approval procedures, potentially extending development timelines. In the absence of an integrated process, developers will likely need to seek separate permits for CO2 storage and geothermal parts of the project. The administrative capacity and expertise of regulatory bodies is also expected to be a factor as understaffing is likely to limit the ability of a regulator to review applications. In addition, such projects will likely prompt the adoption of new impact assessment requirements and safety standards to prevent the leakage of CO2 during the utilization phase. Separately, long-term liability issues will likely need to be addressed to balance public concerns and operator costs. In case CO2 utilization for heat extraction is possible during the post-injection period, the liability of storage and geothermal operators (if they are separate entities) should be delineated clearly, while the transfer of liability to the state is likely to happen after the decommissioning of the geothermal plant.

Public acceptance considerations

Combining CO2 storage with geothermal power generation is likely to amplify public concerns about both technologies and create a challenging environment for project developers. The public acceptance of CCUS plays an important role in project success, but currently the opposition to such projects is primarily focused on pipelines. However, the situation could change when CPG comes into play. One of the strongest concerns associated with geothermal projects is the risk of induced seismicity. In 2009, a geothermal power plant in Basel, Switzerland, was abandoned following a series of earthquakes, one registering magnitude of 3.4 on the Richter scale that damaged properties. More recently, an enhanced geothermal system in the city of Pohang, South Korea, triggered a 5.4-earthquake in 2017, which resulted in 135 people injured, 1,800 people displaced, and cost $123 million in property damages. The perceived risk of an earthquake at a CPG site that could trigger a massive release of carbon dioxide could fuel significant opposition to such a project among local communities, leading to protests and lawsuits.

In addition, there could be perception spillover from fracking onto public perceptions of geothermal projects and, by extension, onto carbon storage and CPG facilities. A study from the United Kingdom found that people who experienced fracking-induced seismicity (or know about it) would have similar concerns about deep geothermal projects, with potentially negative attitudes towards shallow geothermal projects, if there is low level of awareness about different types of geothermal technologies. Therefore, the regions with high levels of opposition to fracking are likely to be a challenge for potential CPG developers. Earlier this year, lawmakers in the state of New York expanded the ban on fracking to include liquid carbon dioxide. The move was prompted by Southern Tier Solutions that intended to use captured CO2 for fracking instead of water to extract natural gas. If public concerns are strong and communities can secure the support of local politicians, the risk of similar restrictions for geothermal projects is likely to be elevated, dimming the prospects for the use of carbon dioxide as heat extraction fluid.