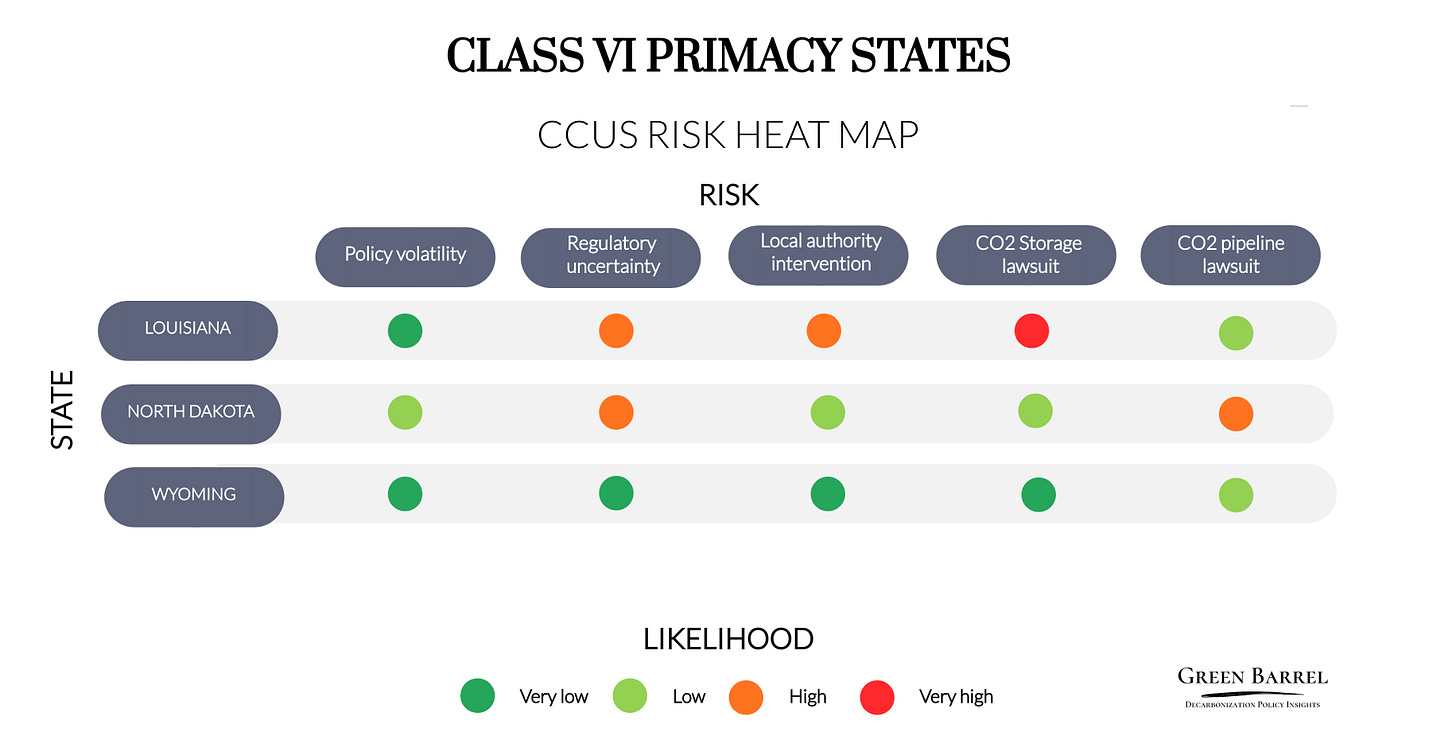

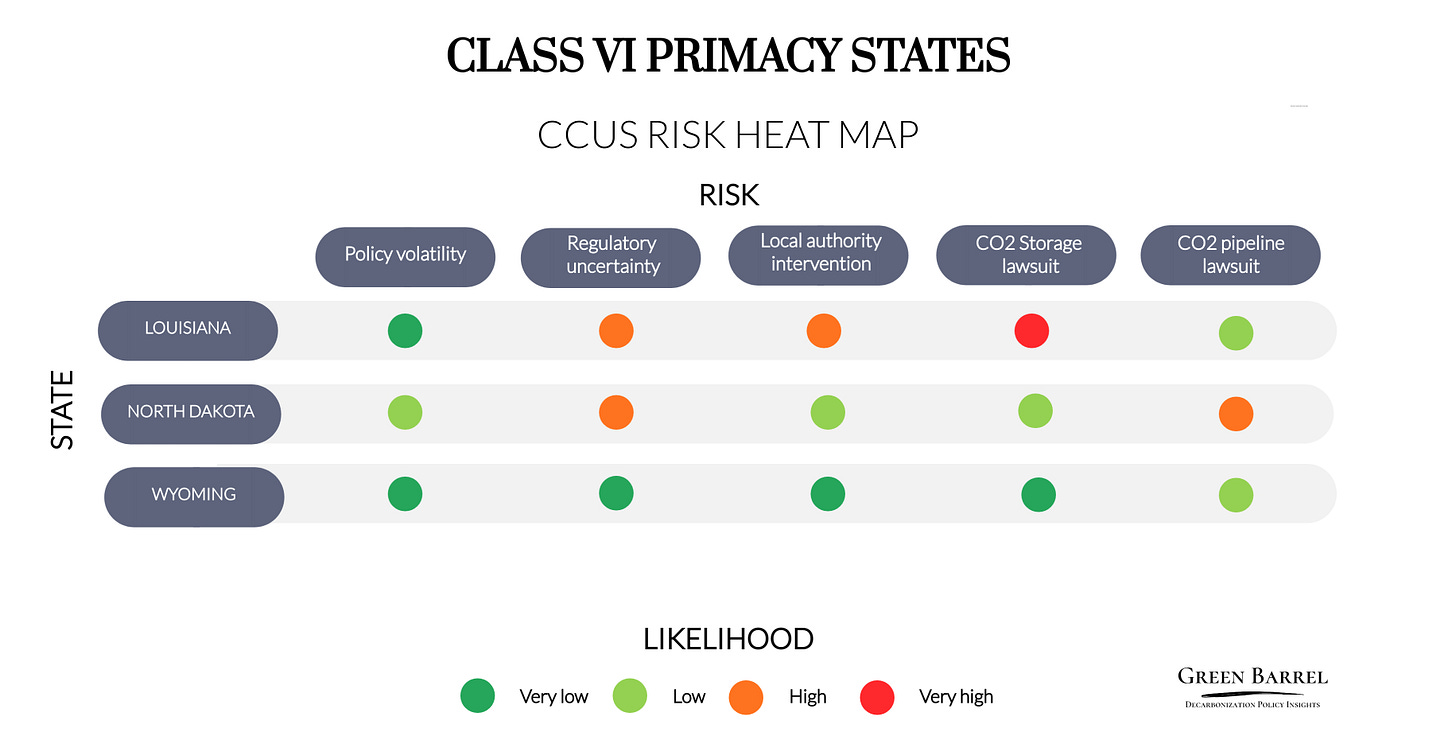

Class VI Primacy States: Risks to CCUS Projects

Primary authority speeds up permitting, but there are other factors at play that could delay project development.

At the end of December 2023, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) granted Louisiana primary authority over Class VI injection wells, which is expected to accelerate the permitting of CO2 storage projects. Moreover, when the EPA completes the transfer of all pending applications (from 22 projects as of December) to the Louisiana Department of Energy and Natural Resources (DENR), it will have more capacity to process project applications from states that fall under federal regulation.

Although Class VI primacy provides a major boost to the relative attractiveness of a state, it is in no way a silver bullet that opens the door to the smooth development of the CCUS industry. Supportive policy environment, mature regulatory framework, and social license to operate represent important factors that could have an impact on the buildout of carbon transport and storage infrastructure. While North Dakota and Wyoming, which also hold Class VI primacy, have a relatively stable environment and established frameworks, the situation in Louisiana is more complicated despite strong political support.

Louisiana: Social license to operate remains in doubt

Local opposition to carbon storage projects is likely to remain a major source of challenges to CCUS investors, leading to potential regulatory delays and lawsuits. In 2023, the environmental and safety concerns, particularly associated with Air Products’ CO2 storage site under Lake Maurepas, prompted a series of legislative proposals in the state legislature that could have put significant limitations on CCUS developments. However, only House Bill 571 made it to the governor’s table and became Act 378 with significant implications for CO2 storage operators. The legislation changed the post-injection period after which a company is allowed to transfer the liability for sequestered CO2 from 10 to 50 years (compared to 10 and 20 years in North Dakota and Wyoming, respectively), added environmental analysis to the Class VI permit application and introduced additional reporting requirements for storage operators.

Separately, Senate Resolution 179 established the Task Force on Local Impacts of Carbon Capture and Sequestration to study the benefits and revenue streams of CCUS projects. The Task Force is required to submit its final report on or before February 15, and its findings could lead to new legislative proposals that would target CO2 regulations in Louisiana. Moreover, several lawmakers remain committed to introducing bills that would tighten regulatory requirements for CCUS developers. However, even if such bills pass the State Legislature, they are likely to be vetoed by Louisiana’s new governor Jeff Landry, who is supportive of CO2 storage projects. In addition, Landry is strongly opposed to the federal government’s climate approach, and in 2022, when he was Louisiana’s Attorney General, led a legal challenge against the Biden administration’s revised estimates of the social cost of carbon. Given the low chances of any major changes via legislation, local activists and environmental groups are expected to resort to legal instruments in an attempt to address multiple concerns.

First, civil society groups are questioning the administrative capacity and the expertise of the DENR staff to review Class VI applications and ensure robust oversight of CO2 injection wells. Some groups, including the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, are committed to scrutinizing the state agency’s management of Class VI wells and would seek the revocation of Louisiana’s primacy in case significant violations are found. Second, there are persistent concerns about the impact of the CO2 storage facility on the ecosystem of Lake Maurepas as well as other economic activities and property values. To mitigate these concerns, Air Products, the company behind the project, launched the Lake Maurepas Community Fund to invest $1 million in community projects annually during the period of the site operation (25 years). In addition, the company provided $9.9 million to Southeastern Louisiana University, which implements the Lake Maurepas Monitoring Project to monitor its health. Still, local residents remain suspicious about the effects of industrial activities on the lake and their livelihood, and protests, lawsuits and interventions by parish councils are likely to remain a risk.

Finally, there is an overall lack of trust in the oil and gas and petrochemical industries among local communities, which have experienced adverse health impacts from poor air quality. EPA’s final rule on Louisiana’s Class VI primacy includes environmental justice provisions, requiring the state to identify potential risks to minority and low-income populations, evaluate well sites using Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool, and hold enhanced public comment period if increased risk factors are found. Activist groups are expected to oversee the enforcement of the requirements and pursue legal action in case of non-compliance.

In addition, CCUS project developers are facing regulatory uncertainty around potential storage sites in the state waters of the Gulf of Mexico due to conflicting interests of different industries. In December 2023, Louisiana granted 60,000 acres to offshore wind developer Vestas. The proposed project partially overlaps with the footprint of two CO2 storage projects, proposed by Venture Global and Castex Carbon Solutions under the seabed south of Cameron Parish. The carbon storage companies entered into agreements with Louisiana before Vestas and both companies are already conducting impact assessments and preparing Class VI applications. The situation could prompt project delays and court proceedings, and the DENR will likely need to ensure clear delineation of seabed uses to prevent future conflicts.

North Dakota: Pipelines could be a major source of risk

The growing number of projects indicates favorable environment for CCUS investment, but local opposition to CO2 pipelines could undermine progress. In November 2023, CO2 injection started at Blue Flint Ethanol facility, while Project Tundra at Milton R. Young Station power generation facility (up to 4 million metric tons of CO2 per year) received a grant from the federal Department of Energy of up to $350 million in December on top of a $150 million loan from the state earlier that year. While CO2 storage projects have not triggered safety or environmental concerns across the state, there are issues around pore space rights that could fuel some regulatory uncertainty.

In mid-2023, the Northwest Landowners Association filed a lawsuit against the state of North Dakota intended to clarify the terms “amalgamation of underground pore space” and “equitable compensation” when the pore space of non-consenting landowners is used. If the court finds that the process of amalgamation is unconstitutional, project developers will have to seek eminent domain authority to access the pore space of non-consenting landowners, which is likely to prompt delays. However, the legal case does not target any carbon storage projects and pursues more safeguards for landowners that could also create a more predictable environment for CCUS developers over the longer term.

In the meantime, the construction of CO2 pipelines is likely to remain an obstacle to projects that aim to store carbon captured from multiple sources across North Dakota and beyond. In August 2023, the Public Service Commission denied Summit Carbon Solutions a permit for its CO2 pipeline project. The state regulator is expected to reconsider the application in 2024, but a positive outcome is not guaranteed, and the company is yet to clear regulatory hurdles in other states through which the pipeline would run. There are ongoing concerns among local residents about the safety of the pipeline and the use of eminent domain powers, which could lead to legal action against Summit and/or the state authorities.

Wyoming: All quiet on the CCUS front

The state has a relatively stable policy and regulatory environment for the CCUS industry, which is expected to persist over the near-to-medium term with a low risk of disruptive events. Wyoming has spent around a decade polishing its regulatory framework and at the end of 2023, the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) issued its first three Class VI permits to Frontier Carbon Solutions LLC. The state is the top coal producer in the country and the bulk of its electricity comes from coal-fired plants. Given the importance of coal to the state economy, in 2020 lawmakers adopted legislation to encourage the retrofitting of coal-fired power plants with carbon capture equipment instead of pre-mature decommissioning. The deadline is 2030 and the latest legislative proposal is seeking to extend it to 2038 and give operators more time to comply with the standard. However, there has been little appetite for such upgrades among power plant operators due to high costs. And while the prospects for storing CO2 from coal-fired plants remain uncertain, Wyoming has the potential to import carbon dioxide from other states that will require the buildout of pipeline infrastructure.

The conversion of the approximately 400-mile-long natural gas pipeline (Trailblazer) to CO2 transport is expected to be a test case for inter-state infrastructure running into Wyoming. The pipeline would transport up to 10 million tons of CO2 per year from Archer Daniels Midland’s corn processing plant in Nebraska via Colorado to the Eastern Wyoming Sequestration Hub. The project is located in the Denver-Julesburg (DJ) Basin and operated by Tallgrass. The company applied for Class VI permits at the end of 2023 and is likely to have them reviewed before the end of 2024, given that it took DEQ ten months to process previous applications.

While public perceptions of CO2 pipelines are unclear, Wyoming has a recent history of fighting energy projects in courts. In May 2023, the state Supreme Court ruled against the group of landowners that challenged the regulator’s approval of a 120-turbine wind farm. There are also concerns among conservation groups about the impacts of new projects on the fragile sagebrush ecosystem. The Nature Conservancy group has an initiative intended to incentivize the siting of renewable energy projects on previously disturbed lands, which would protect untouched ecosystems. Although the conversion pipeline project is unlikely to face opposition as it is already in place, any new carbon dioxide pipelines running in the wildlife areas could spark opposition from conservation groups.

Policy volatility: the risk of unfavorable policy shifts as result of the change in state leadership or the makeup of the legislature.

Regulatory uncertainty: frequently changing regulations or requirements open to multiple interpretations that complicate permitting processes.

Local authority intervention: the risk that a local government body (e.g. county or parish council) imposes additional requirements or attempts to limit operations via regulatory restrictions.

CO2 storage lawsuit: the risk of legal action against a carbon dioxide storage operator.

CO2 pipeline lawsuit: the risk of legal action against a carbon dioxide pipeline operator.

Note: The heat map assesses policy and regulatory environment within a single state. Any negative effects resulting from events in a neighboring state, such as the denial of a pipeline permit, should be evaluated separately.